Grafting

Grafting is a more skilled form of propagation used for woody and herbaceous perennials. While it does require skill and practice, it isn’t the black art that many people think it is and is an ideal method of propagating for most gardeners. The basis of grafting is to attach a ‘rootstock’ of one plant (which includes the roots) to a ‘scion‘ of another (which has all the top growth), so that it forms one new plant. However, the genetic identify of each half remains intact, so the roots will retain the characteristics of the rootstock used, and the top growth will retain the characteristics of the scion.

There are many reasons for grafting plants:

- Where a plant doesn’t root easily by itself.

- To alter the growing characteristics (eg the size) of a plant while retaining the same top growth appearance.

- To provide disease resistance to an otherwise susceptible plant.

- For faster maturation than can be achieved from cuttings.

- To improve cropping of fruit trees.

In order to graft a plant, both the rootstock and scion normally must be from the same species of plant. The process of grafting must be carried out in hygienic conditions and all tools used kept clean and sharp to reduce the risk of diseases entering the graft point. Specialist grafting and budding knives are used to make the cuts.

The graft union forms between the cut ends of the scion and rootstock. As the cut ends heal themselves they create a callus, which is like a scab. Because the two ends are held closely together, the callus cells intermingle, forming the graft. They then differentiate to form a continuum between the tissues of the rootstock and scion (ie to connect up the xylem vessels in each part which carries water up the plant). This basic graft forms within days and will occur more quickly in warmer temperatures.

The grafting cuts must be made quickly and cleanly so that the process is completed before the cut ends can dry out. You should always avoid touching the cut ends in case of infection. When putting the two sections together the cambiums (the rings containing meristematic, or growth, cells just inside the rim of the stem) must be aligned as much as possible. If you have to use two different diameter sections then ensure that the cambium is aligned at least on one side.

Grafting is generally done in late winter to early spring (during a dormant period) or from mid to late summer. Grafting can be done ‘in the field’ whereby the rootstock is left growing in the ground and the scion grafted onto it (this is the usual process for fruit trees) or indoors, when it is called ‘bench grafting’, where the rootstock is growing in a container and the grafted plant is kept in controlled conditions, then hardened off before being planted out.

Rootstocks, particularly for trees, can be purchased from specialist nurseries (ensure you always purchase certified virus free stock) or you can grow your own. Whichever you do, make sure that the rootstock is appropriate for the size and type of plant you want and that it is compatible with the scion. If you’re growing your own rootstock then you can do so from seed, stooling or trench layering. You should aim for rootstock that is well rooted, straight, of medium thickness for the plant in question and about 45cm tall (or taller if required, eg for top working a standard).

The scions should be one year old shoots which are cut just into the older growth at the base of the stem (older growth at the base can help the graft succeed). Keep the scions in a plastic bag or ‘co-extrusion’ bag (which is black on the inside and white on the outside) until you are ready to use them. When selecting scions from conifers, leading shoots should be used (not sideshoots) as sideshoots only tend to grow sideways, even after grafting.

There are various processes used in grafting and different types of cuts:

Grafting processes

- Approach grafting vs detached-scion grafting

- Bottom-working

- Top-working

- Double working

- Grafting multiple scions

- Hot callusing

Grafting cuts

Grafting processes

Approach grafting vs detached-scion grafting

In approach grafting the scion is grown on on its own roots after grafting until the graft union is fully joined. This method is rarely used nowadays although it is sometimes used in grafting tomatoes. When used for tomatoes, a 2cm long downwards slit is cut into the roostock about 8cm from the stem’s base. A mirroring, upwards slit is cut into the scion. The two plants are then joined by slotting the scion down into the roostock and the rootstock top growth cut back so just one leaf remains. Both plants are grown on as the graft union forms. Once heeled, the scion is cut through at the base so the plant grows on just on the rootstock’s roots.

Much more common is the detached-scion method whereby the scion is detached from the parent plant and then grafted onto the roostock. The information below relates to detatched-scion grafting.

Bottom-working

This is the most common form of grafting, where the graft union is made at ground level, so the scion forms the stem or trunk of the plant.

Top-working

This is the opposite of bottom-working, where the graft union is made at the top of the stem or trunk. So the roostock forms the stem/trunk and the scion provides the top growth only.

Double working

This involves using sections from three different plants in one grafting process, meaning you have a rootstock, an interstock and a scion. This is sometimes done to add another characteristic to the plant (eg to reduce the vigour of a fast growing roostock) or were the scion and rootstock are incompatible, but the interstem section is compatible with both.

An example of double working would be with fruiting pears, which are often grafted onto quince rootstocks becaues they are generally more dwarfing and produce better quality fruit. Some pears, such as Pyrus ‘Jargonelle’ or P. ‘Bristol Cross’ are incompatible with quince stocks, and therefore an interstock such as P. ‘Beurré Hardy’ is used.

Grafting multiple scions

Generally done with fruit trees and roses, this process involves grafting scions from more than one variety of the plant onto the same rootstock. This can be done to provide one tree with a variety of fruits (eg peaches and nectarines or different cultivars of apple), to enable cross-fertilisation of fruit on the same tree, or to have more than one colour rose on the same plant. These are also called ‘family trees’. This process may be done on weeping ornamental trees; multiple scions of the same type are grafted to give a more rounded, fuller weeping effect.

Hot callusing

Once a plant has been grafted, applying heat to the graft union can speed up the callusing and healing processes. The grafted plants are leaned against insulated warming pipes or cables, usually going into a slot in the insulation material so that the heat is applied directly to the graft area, rather than to the entire plant. This encourages speedy healing rather than overall growth, which could be to the detriment of forming the graft union.

Grafting cuts

Apical grafts

Apical grafts involve the scion being put directly on top of the rootstock; the top of the rootstock is removed and they are joined end to end.

Spliced side graft

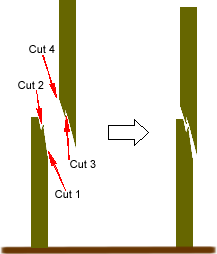

Spliced side graft

Cut the stock back to about 10cm above soil (or leave it longer if you are top-working) then make a small cut angled downwards into the rootstock about 2.5cm from the top of it (cut 1). With the knife almost flat on the stem, remove a sliver of the stem downwards (cut 2), finishing at the base of the first cut. Finally, take another sliver of bark with an upwards motion (cut 3).

Take the scion and cut a shallow, downwards sliver from the end of the scion, starting about 2.5cm from the end (cut 4). Then make a short, downward angled cut from the other side of the scion (cut 5).

The scion should then fit neatly into the rootstock. Bind the graft point with grafting tape, rafia, or rubber grafting bands and seal the area with grafting wax or wound sealant so it is completely covered.

Once the graft has ‘taken’ the fixings can be removed. Any suckers growing from the rootstock should be gently torn off (tearing won’t encourage re-growth like cutting can).

Whip graft

Whip grafting is similar to spliced side grafting, only with a simpler cut, used where the rootstock and scion are exactly the same diameter. Both the rootstock and scion are cut with a slanted cut starting about 2.5cm down one side of the stem and finishing at the tip on the other side and then bound together as for spliced side grafting.

Whip-and-tongue graft

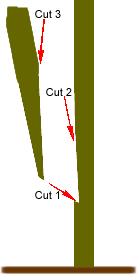

Whip-and-tongue graft

This type of graft cut is often used for field grafting using a rootstock and scion of a similar diameter, and no more than 2.5cm thick. Cut the top off the rootstock at about 15-30cm from ground level (if you are field grafting a tree) and trim off any sideshoots. Make an upward sloping cut one one side of the top of the rootstock, starting about 3.5cm from the top and finishing about half way through the thickness of the rootstock (cut 1). Then make a shallow cut about 5mm deep about one-third down the cut section (cut 2) forming the ‘tongue’.

Trim the scion to 3 or 4 buds and remove any soft top growth (assuming you are grafting a tree) and trim the end so that the bottom bud is about 3.5cm from the base of the scion. Make a slanted cut, starting 3.5cm down on the opposite side to the bud, which goes through the width of the scion (cut 3) and then make a ‘tongue’ to match the roostock about two-thirds down the cut section (cut 4).

The two pieces should then fit together with the tongues overlappig and leaving a small ‘church window’ of exposed stem showing at the top of the graft. Bind together as for spliced side grafts.

Assuming this has been used for tree grafting, select one of the resulting buds on the scion to grow on as the leader to form the stem of the tree, generally the top bud is used. The resulting growth can be tied to a cane to keep it straight.

Apical-wedge graft

Apical-wedge graft

With apical-wedge grafting, which is used for example for avocado trees, the scions are only 15cm long.

A single, long cut (2.5-5cm) is made down through the centre of the rootstock (cut 1).

Then the scion’s base is cut twice (cuts 2 and 3) to form a V shape, which then fits into the rootstock. At the top of each scion cut ‘church window’ semi-circles of cut stem should be visible.

The graft is then tied as for spliced side grafts.

Saddle graft

Saddle graft

This is the like an inverted apical-wedge graft, with the rootstock forming the V shaped end (cuts 1 and 2) and the scion forming the slit for it to fit into (cuts 3 and 4).

This makes it appear that the scion is sitting on top of the rootstock like a saddle.

This results in a strong union as a large amount of the internal stem surfaces are united, but it’s critical to make the cuts match, which makes it difficult to do.

Cleft graft

A cleft graft is a variation on the apical-wedge graft, whereby two scions are prepared from semi-ripe material and both slotted into a single cut made across a thicker rootstock. The two scions should each be lined up flush with each side of the rootstock. This is used, for example, when grafting camellias.

Side grafts

In side grafting the scion is inserted into the side of the rootstock without the top of the rootstock being removed. Once the graft union has formed the top of the rootstock is then cut off.

Spliced side-veneer graft

Spliced side-veneer graft

This method is often used to graft conifers. A slanted downwards cut is made near the base of the rootstock a quarter of the way into the stem (cut 1). A sliver of the stem is then cut from abot 3cm above the first cut, ending where the first cut ends (cut 2).

If the plant is evergreen then the bottom 5cm of leaves/needles are stripped from the scion and a sliver of stem removed about 3cm from the base of the scion, so it is the same size as the cut in the rootstock (cut 3). The scion is then fitted into the cut in the rootstock ensuring that the cambium matches up.

The two pieces are then bound together firmly, but not too tightly, with grafting tape, rafia, or rubber grafting bands and the area should be sealed with grafting wax or wound sealant so it is completely covered.

After about 3 months’ growth and once the scion has put on at least 1cm of new growth (this timescale will vary from plant to plant) the top growth from the roostock should be removed in one or two stages, until the only top growth remaining is that from the scion.

Side-wedge graft

Side-wedge graft

This works on the same principle as the apical-wedge graft, with a slit being made in the rootstock and the scion being cut to form a wedge to put into it, however it is made on the side rather than apex of the sections.

A single, downwards cut is made into the rootstock, going about a quarter into the width of the rootstock (cut 1).

The base of the scion (which has 2 or 3 buds on it) is cut twice (cuts 2 and 3) into a V shape, but where one side is slightly longer than the other. The scion is then wedged into the slot in the rootstock, with the longer scion cut against the rootstock’s stem and the shorter cut lining up with the lip of the rootstock’s stem cut.

T-budding

T-budding

This is the most common grafting method used for modern roses and is generally done in the field. The bud is taken from a vigorous, young scion stem from which the soft top growth and leaves have been removed, but the leaf stalks are retained as these will provide ‘handles’ by which to hold the bud.

Once the stem is ready for the buds to be removed, the rootstock should be prepared. Clear the soil from the base of the rootstock stem and clean the stem to remove the soil and any debris. A 5mm horizontal cut is made at the base of the rootstock (cut 1), then a vertical cut is made upwards to meet the first cut (cut 2), so it forms a T. The bark is gently pealed back from each side of the T, using the blunt edge of the knife, forming a little ‘pocket’.

Now that the rootstock is ready the buds can be taken from the scion stem. Holding one of the leaf stalks with the buds facing upwards, insert the knife about 5mm above the leaf stalk and cut downwards to remove the leaf stalk and about 2.5cm of stem below it. This should be done with a ’scooping’ motion.

Continuing to hold the bud by its tail, carefully peel away the pithy wood which is on the inside of the bud and trim the bottom of the bud so the whole piece is about 1cm long.

The bud is then slid into the T cut on the rootstock, trimming off the top of the bud if it sticks out of the top of the T cut.

A rubber grafting patch should be used to hold the bud in place and protect it from the elements. In colder areas, earth up the soil around the graft area to protect it from frost, uncovering it in the spring. The rubber patch will gradually rot off, revealing the (hopefully!) unified and growing bud. Once the bud is showing a good union and strong growth the rootstock growth can be removed (for roses this is done in early spring when the plant is dormant).

Chip-budding

Chip-budding

The stems which the buds are to come from for chip-budding and the rootstock should be initially prepared in the same was as for T-budding.

The chip-bud should be cut off the stem, starting at the base of the stem, by making a slanted cut into the stem about 2cm below the bud and to a depth of 5mm (cut 1). Then cut into the stem about 4cm above the first cut, drawing the knife down the stem to join the end of the first cut (cut 2).

The rootstock should be prepared with a shallow cut of the same length as the chip-bud (cut 3) and finished by a short inwards cut (cut 4).

The chip-bud can then be placed into the cut in the rootstock (if it’s smaller than the rootstock ensure that the cambium is lined up at least on one side), and bound using grafting tape.

Once the graft union has formed the grafting tape can be removed (generally this takes up to 2 months) and the rootstock’s top growth removed in the late winter or early spring following grafting, once the bud is growing strongly.